A Case Study in Decrepitude

The poor performance of the Russian army has become the surprise consensus of Western war punditry, and while there's plenty of propaganda doing the rounds the use of social media triangulated with multiple reports paints a concerning picture - for the Kremlin. The viral footage of farmers towing away military hardware, of Russian soldiers complaining about being out of gas, and of armoured columns apparently shot up by Ukrainian drones. A Putin propaganda master stroke to lure his opponents and the West into a false sense of security about the quality of Russian arms, or what it immediately appears to be: an incredible display of ineptitude? Perhaps using up a load of fuel and provisions on manoeuvres in the freezing mud of Belarus in the weeks prior to the invasion wasn't the best of ideas.

As Ukraine has proved, no tragedy is without its moments of farce, but even if Putin's forces weren't experiencing the stubborn resistance we're seeing, from the conventional armed sort to human chains blocking convoys on Ukraine's highways to singing the national anthem at bemused Russian troops, that Putin would meet opposition was forecast by everyone with eyes and an internet connection. Putin, who was the world leader Nigel Farage previously most admired because of his acumen and feel for the international scene, grossly underestimated not just Ukraine but the diplomatic wall the West has quickly erected against him.

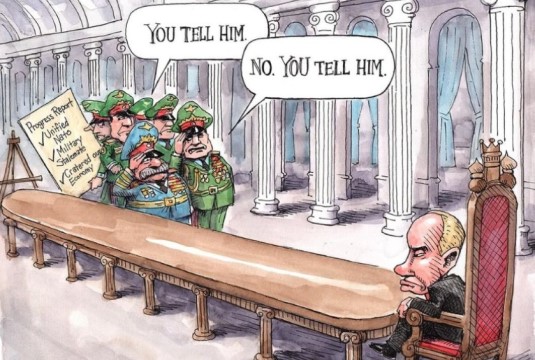

Hubris is one charge laid at Putin. As Ben Judah rightly points out, in recent years the top of the Russian state has undergone significant degeneration. From a mafia council to one boss ruling alone, Putin's closest lieutenants are his creatures bought by office holding and gas money. The oligarchy that supported the regime for so long are at arms length, literally distanced in the case of those domiciled in London or sailing the seven seas on their super yachts, or are either out of sorts or have fallen out with their former champion. Just like political parties in the West who erode as they become cut off from their planks of support and fall prey to their mythologies, it appears Putin has arrived at this destination through a simple process of social distancing, in the non-Covid sense, from his base. This does not mean that Putin lives inside an illusion pushing around imaginary battallions on a map, but it does mean it is distorted. And this helps explain his decision making.

On the Western powers, unfortunately there is a grain of truth in the oft-made warhawk claim about Syria. When Putin threw his support behind Bashar Al-Assad's regime the absence of effective action against the Syrian government precisely because Russia was now involved was obviously noted. The same was probably true of the Salisbury poisonings too. This summer the Anglo-American alliance abandoned Afghanistan to the Taliban and famine, having seemingly lost their resolve to defend their client government. And since 2003, Western publics have grown more wary of military entanglements. Add to this the shocks that have rippled through the body politic over the last decade - Brexit and its bad tempered negotiations, Trump, Corbynism, the collapse of the centre left in Europe, so-called culture wars, divisive referenda, and the fall out from Covid all, from the end of Putin's overlong table it looks like his traditional opponents are in a state of disarray. And then there are Russia's recent military adventures. The ghost of the first Chechen war was put to rest by the shock and awe brutality of the second. Then there was the short, sharp police action against Georgia which set up puppet regimes in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and then the swift annexation of Crimea which was relatively hassle-free. The relatively low level war in Ukraine's eastern breakaway republics notwithstanding, this run of operational luck can inflate the perception of a military in the eyes of its commander-in-chief. Faced with an apparently divided West and a Ukraine that didn't put up much resistance to the bites Putin took out of it in 2014, living in splendid isolation with yes men spinning the military intelligence reports, we get some way along the road to understanding the conditions of Putin's thinking, and the grounds of his miscalculation.

What Putin got wrong was, obviously, Ukraine's resolve. With a better equipped and a larger army than eight years ago, plus a motivated population determined to push out an invader, it should have been obvious to everyone, especially someone historically as savvy as Putin, that the force assembled was not up to the task of subduing a large country. The second is his misreading of the West. While he was right NATO and the EU would not commit troops to fight in Ukraine, he miscalculated its appetite for sanctions, even if they caused the West some inconvenience. And he got this wrong because it directly confronted the common foreign policy interests of Europe and the United States. The West was and is divided over what to do in the Middle East, but not when it comes to containing Putin's revanchism on its eastern frontier. Putin is forcibly trying to remove an EU-NATO client state from the West's orbit for a Russia-friendly, dismembered buffer state. He is therefore confronting Western interests directly, and they will not countenance it. And given their collective economic and soft power clout, the other major world powers - India and China - are observing something of a Trappist silence with Xi, apparently, very displeased with Putin's adventure. They have used their influence to diplomatically isolate Russa like no big power has been since the Second World War. It didn't take genius insight to read where the tensions are and where there is unity among the Western alliance, but this is exactly what the Kremlin has failed to do.

The grey beards liked to talk about the materialism of historical processes, how social being conditions consciousness. To put it crudely, ideas don't drive history. Rather it is history that gives rise to thought. In Vladimir Putin, we see this play out like simple chemistry experiments in a laboratory. The decay of post-Soviet Russia was exacerbated by the class he championed and the state he contructed. The looting of his country's wealth and its disappearance into certain jurisdictions has left Russian infrastructure in a state of advanced disrepair, and the rot has spread throughout the political body, from the corruption of the state to the decrepitude of the military. This decomposition he and his cronies have overseen and profited from has boomeranged back, conditioning the thinking behind what is an egregious miscalculation. Putin has made a serious mistake that could cut short his time at the top, and one ensuring a river of blood lies between now and the consequences of his actions catching up with him.